By Patrick Dearen

It was a cattle drift for the ages, displacing countless thousands of beeves, and one man emerged as the “hero” in their return from the Pecos. Gus O’keefe.

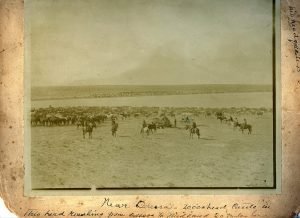

Known as the Big Drift of 1884-85, this massive migration cost cowmen thousands of cattle, but the losses would have been greater if not for Christopher Augustus “Gus” O’Keefe, who ramrodded the subsequent roundup along the river. Detail-oriented and a good judge of men, Gus could “get more work done than anybody,” recalled his brother Rufe.

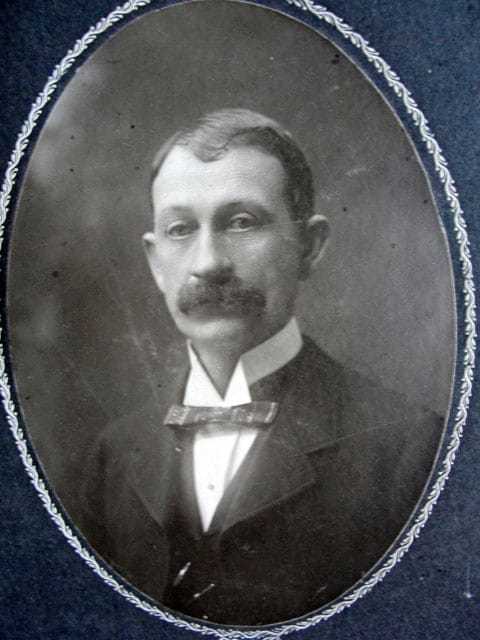

The only known photograph of this unrivaled roundup is in the Haley Library’s Scharbauer Family Collection. Showing a portion of a drive herd 20 miles long and containing 20,000 cattle, it speaks to Gus’s remarkable cow-sense and resourcefulness, attributes he had honed since boyhood.

Born February 26, 1852 in Alabama, Gus O’Keefe lost his father at age five. Upon his mother’s remarriage to James H. Bell in 1865, Gus and his family relocated to Bell’s residence, 25 miles away in Cleburne, Alabama. Thirteen at the time, Gus gained experience as a trail hand by helping his younger brother David (Dave) drive the milk cows to their new home.

In the late 1860s, with Bell considering a family move to Minnesota, Gus and his older brother James set out in advance for the Land of 10,000 Lakes. They traveled by boat from Jackson, Mississippi to Cairo, Illinois, by train from there to Keokuk, Iowa, and by boat again on to St. Cloud, Minnesota. Gus, still only 17 in 1869, worked alongside James in the fields, where they cut wheat and bound it by hand. Embarking from Duluth during the cold winter, they freighted railroad crossties by sled across a frozen bay of Lake Superior to Superior, Wisconsin.

When their family decided against relocating to Minnesota, the brothers took stock of their circumstances. Not only did they not like Minnesota, but smallpox in the region had reached an epidemic level. They journeyed down the Mississippi River by boat as far as St. Louis, and then struck out overland for Texas. Trekking much of the way by foot, they joined with a wagoner at one point and drove his cattle as far as Little Rock, Arkansas.

Gus and James arrived in Texas in Red River County later in 1869 and subsequently moved to Sherman. After their icy experience in Minnesota, the brothers wrote so glowingly of Texas that their brother Dave joined them in 1872. In the fall of 1874, the three young men traveled south to the cotton fields of Robinson County, but arrived too late to get jobs. Only Gus’s youngest brother, 17-year-old Rufe, remained in Alabama, but he too headed out for Texas, where he met up with his siblings in Waxahachie on Christmas Eve.

A year later Gus was still in the Waxahachie area, but by early 1878 he had ventured to Mitchell County in West Texas and hired on as a cowhand for George W. Waddell and J. F. Byler, who grazed 7,000 cattle along Champion Creek. Two of Gus’s brothers, Dave and Rufe, also rode for the Waddell and Byler brand, although Rufe’s stay with the outfit was brief.

Sometime after the fall of 1878, Gus O’Keefe signed on with C. C. Slaughter’s Long S Ranch, which sprawled across Mitchell and Howard counties. At first, headquarters was 35 miles from later-Colorado City, but Slaughter eventually moved his base of operations to the Colorado River-Bull Creek confluence 20 miles north of Big Spring.

Gus, gifted with business acumen and a cowman’s instincts, so proved his worth that Slaughter selected him as ranch manager, a position that allowed Gus to acquire a one-sixth interest in Slaughter’s 40,000 or more cattle.

Although Slaughter was the ultimate decision-maker, recalled Rufe O’Keefe in Cowboy Life, “he almost always wanted to get Gus’s ideas too. . . . Both of their heads was full of plans and schemes. They certainly did make a good strong combination, if they did differ sometimes. . . . Slaughter engineered the thing; Gus worked out the details and ran the ranch.”

These were open-range days on the Great Plains, with fences generally limited to widely separated drift fences designed to prevent herds from migrating too far south during the winter. One Texas Panhandle fence, likely typical, consisted of four strands of barbed wire stretched between posts spaced 33 feet apart—a structure adequate for a normal drift, but completely insufficient for what happened in the winter of 1884-85.

It shrieked out of the northeast and struck the Plains, a blizzard that set cattle fleeing through the massing snow, an instinctive response to a numbing storm. With tails to the wind and nostrils flaring, the animals marched day after day, their home ranges receding behind them. They came out of Kansas and southeast Colorado, out of modern-day Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle, an onslaught of clashing horns not to be denied.

It shrieked out of the northeast and struck the Plains, a blizzard that set cattle fleeing through the massing snow, an instinctive response to a numbing storm. With tails to the wind and nostrils flaring, the animals marched day after day, their home ranges receding behind them. They came out of Kansas and southeast Colorado, out of modern-day Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle, an onslaught of clashing horns not to be denied.

“They soon created a force that was irresistible,” eyewitness R. M. Clayton wrote in 1930 of the drift through Fisher County in Texas. “You could not stop them, and if you did, there were so many of them that they would soon all have died for want of grass and water.”

Cowhands, said Clayton, had no choice but to “let them keep moving and try to take care of themselves the best they could until spring.”

Wherever this invading army struck a drift fence, the lead animals bunched up and suffocated, their nostrils frozen shut. Some cattle remained standing even in death, macabre monuments to the power of this storm. Countless others died in piles against the barbed wire, creating staircases by which thousands of trailing beeves bridged the barrier.

One flank of the drift bore straight through West Texas into San Angelo, where the animals deluged the town in their unstoppable march. “The downtown streets were just choked with cattle,” said Felix Probandt, a resident of San Angelo at the time. “[They] extended on both sides of Chadbourne [Street] for several blocks.”

Will C. Jones, ranching on the South Concho River below San Angelo, watched the beeves pass by “for a full day and a night without a break, animal after animal in an unbroken stream of cattle that went on south,” he told J. Evetts Haley in 1946.

Not until the beeves reached the Devils and Nueces rivers did they finally cease their flight.

Meanwhile, thousands of other cattle crossed the Texas Pacific track near Odessa and trampled out a mile-wide trail in an 18-inch snow. Reaching the Pecos, the bawling animals bunched up along the sheer bank for mile after mile, with some cattle never halting until they gained the river’s mouth, hundreds of miles from their home ranges.

Weakened by storm and march, the drift herds soon grazed the Pecos flats bare and died by the thousands, a Big Die-Up on the heels of the Big Drift.

“You couldn’t get farther than 10 feet from a dead cow in the river,” Tom Love recalled in a September 30, 1927 interview with J. Evetts Haley. “We had to drink that water. It was full of hair, and all we [could] do was strain that hair and drink it.”

The health hazards of the Big Die-Up were far-reaching.

“So many cattle have died during the past winter in some portions of Texas that local papers are urging the burning or burying of the carcasses lest the public health should be affected by the decaying bodies,” reported The Globe Live Stock Journal on March 31, 1885.

With carcasses mounting by the day on the Pecos and buzzards wheeling in the sky, desperate cowmen met in Colorado (later Colorado City) in late winter and selected the one man capable of organizing an unprecedented roundup on the Pecos—Gus O’Keefe. Facing a formidable foe in a river that Charles Goodnight called “the graveyard of the cowman’s hopes,” Gus set out by rail to evaluate matters. Returning, he implemented a carefully devised plan to flood the stream with unheard-of numbers of roundup hands.

Supervising from Odessa, Gus sent at least 27 wagon outfits with 200 or more men and 1,000 saddle horses. Arriving at the Pecos, these cowboys from far-flung ranches followed Gus’s instructions and rounded up without consideration to brand. From the reach of river that included Horsehead Crossing, they drove herd after herd back toward Odessa and Midland. At intervals, Gus arranged for relay outfits to assume charge of the herds for the march on to the Colorado River breaks, where cowhands would turn the animals loose for later sorting.

The above-referenced photo in the Haley archives offers intriguing insight into what was likely the most demanding of these drives. On the margin of the original photograph is a notation: “Near Odessa—20,000 head cattle in this herd reaching from Odessa to Midland 20 miles long.” Sheepman H. N. Garrett, who saw this herd, recalled in 1908 that it required the attention of 125 drovers as the cattle bore east in a three-mile-wide swath at a rate that required fourteen hours to pass a specific location.

“It was the biggest bunch of cattle I ever saw in my life,” Garrett recalled in the Texas Stockman-Journal of August 5, 1908.

Tom Love, who was with the herd, recalled following a thirsty course to the Colorado breaks that passed just north of the young cowtown of Midland.

“My outfit drove drags,” he related. “. . . We couldn’t force the cattle, so we just drifted them. When they wanted to move, we kept them headed in the right direction, and when they wanted to stop, we stopped with them. . . . When one would drop out, we’d pay no attention to it.”

Finally they reached the Colorado River with the stragglers, a full eight to ten hours after the stronger animals had arrived. It had been a brutal ordeal on the cattle, but the cowhands had suffered as well. “We were about three days and nights,” said Love. “. . . [The] boys were nearly dead for sleep.”

By July, this greatest of all roundups was finally over. Participating drover H. M. Hill estimated that he had helped push an astounding 120,000 to 150,000 cattle off the Pecos, but losses were nevertheless stunning.

“There were more of these cattle drowned and died in the Pecos than ever were brought back home,” noted cowhand Walter C. Cochran.

If not for Gus O’Keefe, however, losses would have been even more devastating.

“[He] was the real hero,” Big Drift eyewitness R. M. Clayton said. “. . . This was where Gus O’Keefe showed his wonderful capacity in handling big things.”

The events surrounding the Big Drift set the stage for Gus’s succeeding decades in the cattle business. After cattle prices plunged in November 1887 and creditors pressured Slaughter, Gus covered the debts on a case-by-case basis by selling the required number of cattle. With prices still low in 1888 and land available at a discount, he left the Slaughter operation and acquired the C A Ranch near Colorado City.

He also found time for romance. In Colorado City in March 1891, the 39-year-old cowman married Josephine McMillon, 13 years his junior and the granddaughter of a Methodist pastor. The union brought Gus and Josie (as she was known) three daughters and two sons, who lived their early years in the family home at Colorado City.

In the 1890s, Gus added to his range by purchasing the Fish Ranch in Dawson County, with some of his 7,000 cattle grazing in northeast Gaines County. Although Gus continued to be highly respected as a cattleman in the early 20th century, he was a dedicated family man as well, and in 1905 the lure of better schools led him to move to Fort Worth with Josie and the children.

The city promised an easier life for Gus, but long years in the saddle had taken a toll. Soon after he relocated, illness and infirmity struck, afflicting him so severely that he was often bedridden. Still, he stayed active in business affairs, particularly in Fort Worth real estate. Most notably, he was developer for the city’s renowned Blackstone Hotel, which Gus named after visiting the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago.

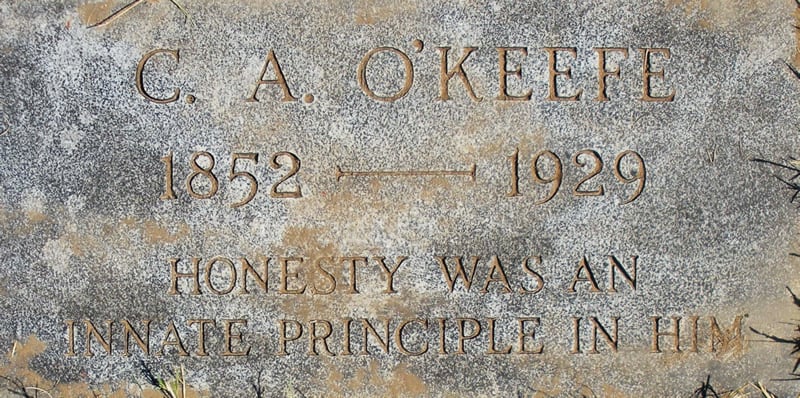

On December 24, 1929, two and a half months after the Fort Worth Blackstone held its grand opening, Gus died at age 77 in Fort Worth. His gravestone in Fort Worth’s Shannon Rose Hill Memorial Park speaks to a character trait common in cattlemen of his ilk, men who faced challenges and adversity but held fast to courage, optimism, and a sense of honor.

“Honesty,” it reads, “was an innate principle in him.”

Sources

R. M. Clayton, letter, 1930, quoted in “Big Blizzard of ’85 Worst Disaster Ever,” Sweetwater Reporter, 17 January 1949; H. M. Hill, interview by J. Evetts Haley, Midland, Texas, 9 September 1931; Will C. Jones, interview by J. Evetts Haley, San Angelo, Texas, 20 November 1946, Haley Library; Felix Probandt, interview by J. Evetts Haley, San Angelo, 30 June 1946, Haley Library; Tom Love, interview by J. Evetts Haley, 30 September 1927, Haley Library; Dodge City Times, as quoted in Texas Live Stock Journal, 13 January 1886, p. 3 and cited in David L. Wheeler, “The Texas Panhandle Drift Fences,” Panhandle-Plains Historical Review LV 1982, 25-35; W. C. Cochran, “Walter C. Cochran’s Memoirs of Early Day Cattlemen,” Betty Orbeck, ed., The Texas Permian Historical Annual Vol. 1, No. 1 (August 1961), 38; Southwestern Stockman as quoted in The Globe Live Stock Journal, 31 March 1885; Texas Stockman-Journal, 5 August 1908; Patrick Dearen, A Cowboy of the Pecos (Helena: Lone Star Books, 2017 edition), 139-148; Patrick Dearen, Devils River: Treacherous Twin to the Pecos, 1535-1900 (Fort Worth: TCU Press, 2011), 130-133; “Panhandle Free Grassers,” Dallas Morning News, 29 November 1885; Hereford Reporter, 31 May 1901; The Seminole Sentinel, 9 July 1989, citing a 1946 manuscript; “James E. O’Keefe, 91, Passes Away,” The Panhandle Herald, 12 January 1940; Rufe O’Keefe, Cowboy Life (San Antonio: The Naylor Company, 1936); Brenda S. McClurkin and Historic Fort Worth, Inc., Fort Worth’s Quality Hill (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2014), 122-124; David J. Murrah, C.C. Slaughter: Rancher, Banker, Baptist (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012 edition), 37, 39; “C.A. O’Keefe, Rancher, Oil Man, Builder, Dies,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 25 December 1929 (http://hometownbyhandlebar.com/?p=12752, accessed 12 December 2016); and photo of C. A. O’Keefe’s grave marker in Shannon Rose Hill Memorial Park in Fort Worth, Texas (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=23711094&PIpi=106713971, accessed 14 December 2016).